Dan Geva aus Israel präsentierte den Film "Description of a Memory" auf dem Dok Fest 2008, München. Der Film setzt sich mit den Träume und Hoffnungen Israels kurz nach seiner Gründung im Vergleich zur Realität heute auseinander.

MC: When and why did you come up with the idea to make a movie on the basis of "Description of a Struggle" by Chris Marker?

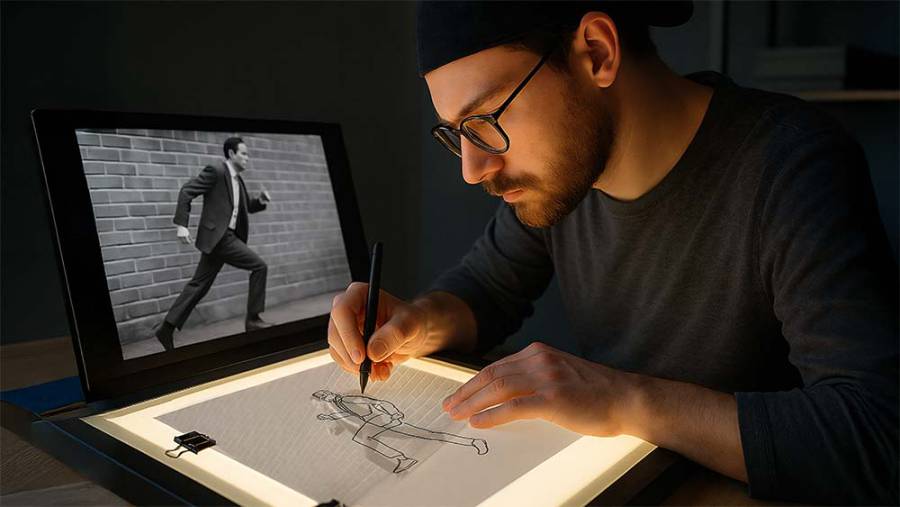

DG: I first saw "Description of a Struggle" when I was around twelve. I can say in perspective that the images of this film magically haunted me. They remained within the hard disc of my memory, long before I was thinking even about film or filmmaking. There came a moment where I felt I don't know what kind of films I can do anymore because I did a lot films about stories, telling stories about living people. At a certain point I felt I am tired of this way of documenting. Because I felt this way makes it easy for people to believe that the stories I am telling are true. And I came to realize that filmmaking is maybe more then that. And then I recalled the film by "Chris Marker", which opens with the line "this land", and he refers to Israel, " this land speaks to you in the language of signs". Now if you come to think about this verse, it's pretty enigmatic, what does it mean? And it really captured me again. I felt he is transmitting a code to me, that will enable me to get through my stage of not knowing how to deal with the documentary form anymore. So this code was a massage, which I tried to decipher. And at that point when I got the message of this code "this land speaks to you in the language of signs", I knew I have to make a film. I have to decipher this code because I was born in this land. And the question, which arose to me, is, what does it mean? And also as a filmmaker, it's a very crucial question, what does it mean that a land, a space, the world in front of you speaks to you in the language of signs. That is a very subversive challenge. I felt I had to deal with it. And it changed to whole way I was looking on documentary filmmaking.

MC: Is there anything special you want to tell the people?

DG: It would be really arrogant of me or, I think, of any filmmaker to say, I want to say something in special because every person in the audience picks up something. The thought that a film or any artistic piece could bare one message and you have the ability to transform it, I think, is naïve and dangerous in many ways. Or the piece you are making is so simple or simplistic that it might be so like in propaganda. But when you deal with true artistic work and you try to compose a complex message then you cannot expect to transform one thing. But what I did want is the audience to plunge into the world of signs. Maybe there is one message and that is not to look at reality in front of them in a very naïve way, in terms of what you see is what there is. Rather the image in front of you and I am talking about any image is just a code to many things that you don't see necessarily and you have to interpret them. You have the mission to interpret the signs, the visual sings, that are not that clear as it seems. And it's hard work. And it's not easy. And most of us are too lazy. I mean all of us in every day life. We don't have the energy to make a deep meaningful analysis of the signs around us. We just say, give me Mc Donald's. You know, I am fine with it. I'll just take the MTV. So this film is a challenge to confront the complexity of the world as a set of signs.

MC: Which role does the drawing girl play in your movie? Can you put her in contrast to all the portrayed men?

DG: The girl has a key role because Chris Marker chose her as a symbol, as a sign to Israel's future. And he put 2000 years of history on the shoulders of this swan girl, very delicate, very fragile. And he said this image bares the whole consequence of 2000 years and the future of this experiment called Israel. Because you have to understand, to "Chris Marker" Israel is an experiment, an experiment in history, an experiment in aesthetics and ethical experiment. And he condensed all the essence of this experiment to all of us, to all nations. That's what it means. It's not an experiment to us Jews in Israel, or you German people, or the English. And he says that that deliberately to all nations. Why? Because all of you nations be at fault of what has happened to the Jews. Now, when they have a state for the first time after 2000 years, let's see how they deal with it. Deal with it, I mean in the sense of, now that they have a state of their own, let' see if they can handle it right where we all failed before. So it's really one of the most severe ethical battles of the 20th century and if you want, of the whole mankind history. The girl has it all on her shoulders without even realizing it. She didn't even know about it. He imposed it on her. I had to find her to see what the fate of that sign was.

MC: How much time did you spend on research?

Fifteen years.

MC: How long was the shooting and editing period?

DG: All together 15 years but the most condensed period was two years. I shot for this film more than 160 hours. Not because I didn't know what I was doing because I realized it had to be experimented all the way through. It was not the kind of a film where you shoot a storyboard or a story that you know. I had to explore my capacity to capture signs in my reality to the very extreme. And it took me many, many hours and days and months and years to clarify the visual code, that is the most difficult thing in filmmaking clarifying and crystallizing the code you want to use, the form, really crystallizing it. Not just like I'll use this, I'll use that, this is nice, like a mixed Greek salad. It doesn't work like that. Most of the effort was to really make it clear.

MC: How important is it to you to question the traditional way of story telling?

DG: It is the most important thing. I would say it's the only thing that matters for me now. And the reason is that the traditional way of story telling is not the right one nor the better one nor a good one. It's just traditional because it was there before. If you as a filmmaker obey the tradition as a priority approach, you might as well be a worker in a can factory because you are just reproducing known patterns. What's the sense? You are doing reportage. But if you see documentary as a form of art, if you do that, you have no other option but constantly researching and exploring the traditional form and contradicting it and trying forms which you yourself believe don't work. That is the most important thing, because you can not go on just wanting to entertain people. We live in a world where entertainment has conquered the mass media. It's all entertainment, even the news, even Saddam Hussein being hanged. Everything is entertainment. War is entertainment. War is part of the entertainment division in Hollywood. The American president consults with the Hollywood script writers how to script the war. It's all entertainment. I truly believe that documentary is a last sanctuary of true artistic expression. And if it will really want to easily and smoothly and nicely and kindly entertain the crowd and please people in known forms, it will freeze and die. Or it will just vanish, mold into other less refined forms of expression like news, like long reportages. And I believe documentaries are not that. That is the mission.

MC: How would you define documentaries?

DG: I would just define it as a huge range of potentialities. It's just there for you to explore its range, potentialities of energies.

MC: How difficult is it to film in Israel?

DG: Not more difficult than anywhere else. I've just filmed something in England, in London. And I thought untill I filmed in London, Israel is difficult. Wait untill you go to London. This is like "1985" by "George Orwell", as a joke, compared to what is happening in London. The whole center of London is covered with secret cameras and you cannot film without all the authorisations, they jump on you right in the middle of the street. They see you from the sky. The whole world is becoming very difficult to film. Documenting freely is very difficult our days because people are very aware, are very aware to the option and potential of abuse of camera. And therefore they are cautious and if you compare the people, the ordinary men in the street in 1960 and 2008, these are two different species. They understand the camera differently. Today people think law suits. They think of, what is my right? Can I or is there is a ring tone in the back? It's very complexed. The whole notion of authenticity of real life, real people has evolved in such a radical way that I don't know anymore, what is the naïve concept of realtiy. Nobody knows I dare to say.

MC: Most of your pictures were recorded with a fisheye lense. Why did you choose this effect?

DG: For two reasons: One is that I was looking for a way to distinguish my view, my vision, my optical approach, my static approach from Chris Marker. Chris Marker is a genius of images, a genius camera man. And he came to Israel and in this film he put together perfect esthetics of his kind. One cannot do it better. And this perfection striked me. I told you it took me 15 years making the film. For many years I just coulnd't face it from an eye level because it was so perfect. That I said how can I touch it? How can I speak with it? How can I dialogue it? How can I intertwine within these images? They are so perfect. They are untouchable. My solution, and that's one of the reasons why it took me 160 hours of filmning, was to realize I have to find a contradictive visual approach to Chris Marker. The ultrawide fisheye represents a decision, a recognition. The recognitions is that Chris Marker as a stranger, as a voyager, as a visiter in my country did not know the people. When you don't know something you take a distance, you go back a little bit and you look at it from a distance to get perspective because this subject doesn't know you. It's kind of a safety distance. All this film is shot within the perfect distance a stranger needs has. I am not a stranger. For good and for the bad. So I took the oposite position of a local and I used the fisheye. And the fisheye forces you to get as close as possible to your subject. The wider the angle is, the closer you have to get, to get a close-up, to get a face, to get an impression. And I wanted to get close. One because I felt very distant. I felt very alienated. I was looking for a way to get closer. The fisheye paradoxicaly enough forced me to get closer. As close as physical closeness could be. I was filming from that distance. And this kind of encounter, I knew, gives me the ethical advantage or ethical right over Chris Marker. Because I was asking, why should this film be done? And the answer I gave myself id because I can show, or investigate Israel, or myself, or my memory in a way he couldn't fifty years ago. So it had to be the widest angle there is. Otherwise it would be bullshit. And that's why I used the ultra fisheye, which is distortive by nature. But just very intimate because when a person just stands that close to you for one minute, two minutes and looks into the lense something very truthful comes out. Apperently it's very distorting but essentially it's very, very intimate. There you have a collision, which is the foundation for any way of phrasing thing in art. Making things collide and crash into one onther. The wide angle is to make this crash very distorted, very alienated and very intimate.

MC: How did you work with sound in your movie?

DG: Most of the sound work was done in the post production. I recorded but very freely because I knew I am going to use the Chris Marker method, which is creating the sound as a world of its own in the postproduction because I didn't interview people and very, very few of the scenes are live scenes. Most of the sound was redesigned, reinvented, remoulded in the editing room, which is the most fun.

Are there any advices you can give to young documentary directors? Yes. Don't give up. It's really difficult in understanding the most important concept of documentary and that is time. The most important concept in documentary is to understand is the meaning and the importance of time. Time in documentary is the one key element because it's an art in time film. But in order to differentiate documentary from all the other types of reportage, documentary takes time, a lot of patience and a lot of insurance. And I think it's very hard for a young person, for anybody, but especially for young filmmakers, who want to make it quickly. I think it's very hard to understand, the crucial role that they have to give to that phrase, take your time, don't hurry. If you shoot, finish your shooting and let the material sink for a while until you get perspective. And then when you edit, don't rush, wait. You finished one version, go have a coffe, go to the beach, start another project, break up with you girlfriend, fight with your father and mother, call something to stir up your perspective of life so that you will be able to return to that material from a different perspective. That is the most important message.

MC: Do you already have plans for a new project?

DG: Yes. I have to have one. One should have always the idea for a next one otherwise is death sentence. The process of making films is always engaged. You make one film and as you are working on it and you are lost and you don't know what the hell will happen with it. You have to have that thing that will pour you to the next one, always. Not to be more productive financally, in your mind, mentally, you have to be able to conceive the next idea to dream about. Otherwise you are just dealing with the solutions that need to be made, in the one you are drowning in. I asked Chris Marker, when I met him, about the experience of a editing because he edits his own films and he is a true master at it. I asked him how do you feel when you are editing. He says, 99 percent of the time, I feel like water is right up to here [points at his forehead], which I found the most exact way of expressing my own feelings. It's really hard when you edit, you barely breath because the material confronts you and doesn't let you be as smart as you thought when you conceived the idea or when you shot it. Oh, yes I got it all figured it out. Once you enter the edinting room the material gets a life of its own and the ghosts and the devils start to whisper all around, you will not win me so easily. So most of the time I agree with Chris when you are up to here, that's why you need a new idea to make you believe that you can conquer the mountain and not drown in the sea.

MC: Thank you for the interview.